All is not yet lost

Conspiracy theories more often than not feed off each other. But hope is not lost.

Team Leibniz Lab Hamburg with Kai Sassenberg (second from left) and Stephan Lewandowsky (center).

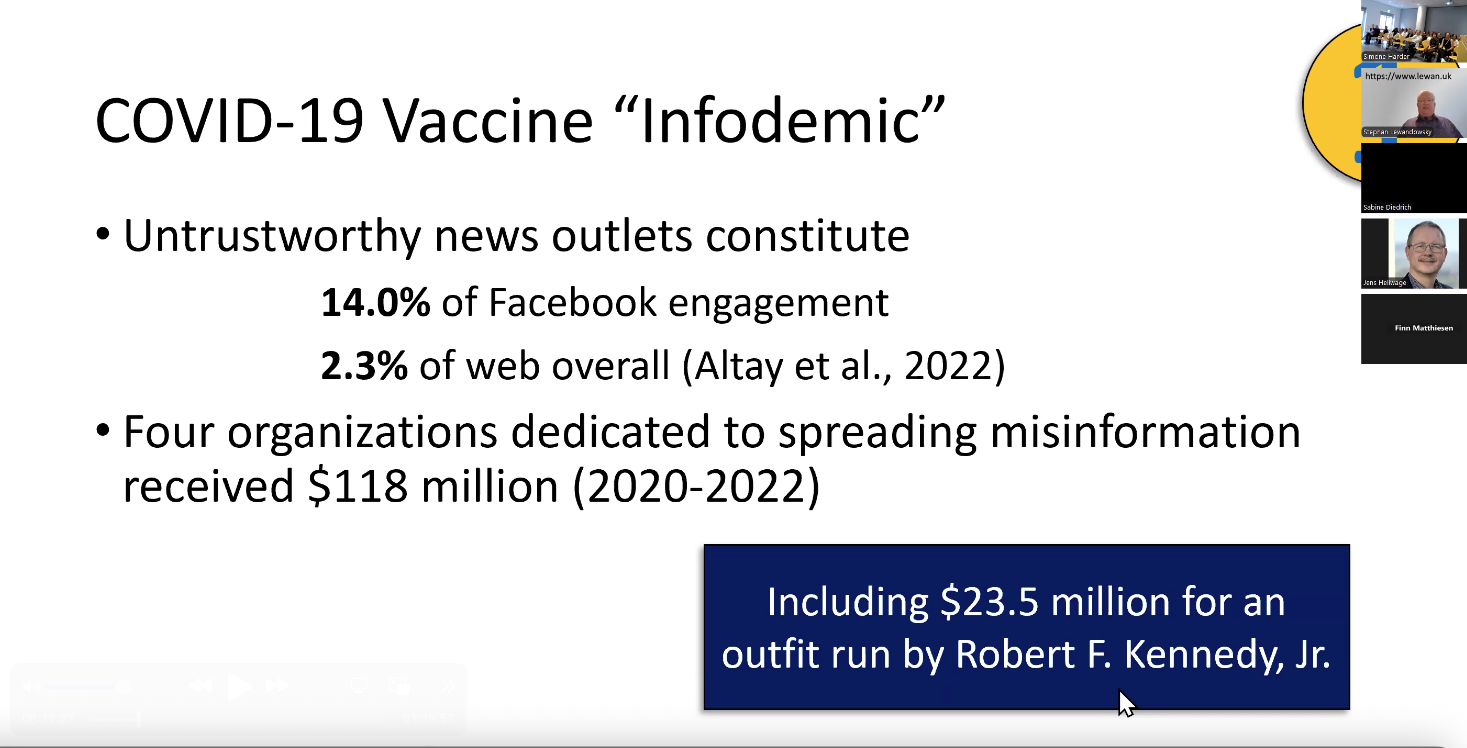

The lecture “Vaccine Hesitancy: Context, Consequences and Countermeasures” gets straight to the point. On one of his first slides, Stephan Lewandowsky quotes the WHO: “We're not just fighting a pandemic, we're fighting an infodemic.” The words of Tedros Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the WHO, stood out at the 2020 Munich Security Conference — and the context made clear that this is more than just a public health issue.

Fake news, misinformation, and conspiracy theories are spreading rapidly in the age of social media — and have surged since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The situation is worrying because misinformation doesn’t simply appear out of nowhere. It is sometimes orchestrated, often with a specific goal in mind. And one conspiracy theory rarely stands alone. Those who reject vaccinations are more likely to deny climate change and often amplify Russian propaganda. One marginalized narrative leads to another — because it’s easier to jump from one untruth to the next than to find a way back to the truth. After all, the truth has already been discredited as “mainstream thinking.” This has now been well documented and researched. You can read about it here ⬇️

Stephan Lewandowsky, professor at the University of Bristol, serves on the Leibniz Lab's scientific advisory board.

The narrative of rejection is often the same — and the storytelling follows a familiar pattern. The conviction behind it all: the mainstream media and the government are lying. This belief is cultivated and amplified online. For example, Florian Philippot, the strategist who “de-demonized” Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National—arguing that right-wing populists can think whatever they want as long as they avoid saying it publicly to remain electable—tweeted in March 2022, shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine: “They lied like crazy about Covid for two years and now they're telling the truth about the Ukraine crisis? Come on.”

Potential conflicts between the architecture of our online information ecosystems and democracy are also a central concern in Lewandowsky’s work. Disinformation in the health sector not only undermines trust in health institutions and public health programs, but ultimately erodes confidence in government structures themselves — jeopardizing democracy in the process.

We are already in the midst of an information war

Potential conflicts between the architecture of our online information ecosystems and democracy are also a key focus of Lewandowsky’s work. Disinformation in the health sector does not only undermine trust in health institutions and public health programs—it also erodes confidence in government structures themselves. And that, in turn, jeopardizes democracy.

The quote from the WHO Director-General sets the tone. The next sixty minutes are not just about vaccinations; the picture is much bigger than that.

An example from Lewandowsky’s work:

(The images in the slides are screenshots from the presentation, which is why online participants can be seen in the bar on the right).

Now, 14% may not seem like much, and 2.3 % even less, but measured against the sheer volume of content published every day, it amounts to a flood of misinformation.Especially in an age where a ready-made digital ecosystem — Facebook groups, Instagram channels, and a range of so-called “alternative” networks — provides a seamless transition from one falsehood to another. The infrastructure is already in place. So are the points of contact.

Shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, conspiracy-oriented groups on social media began repurposing familiar narratives from anti-vaccine disinformation. Suddenly, Putin was portrayed as fighting the “deep state” in Ukraine, allegedly targeting “bioweapons laboratories” in Donbass. That narrative didn’t arise in a vacuum. It echoed propaganda from the Kremlin itself, which accused the US and Germany of maintaining biological weapons labs in Ukraine.

Nonsense doesn’t become true just because the stage is global. Russia presents its so-called “evidence” of biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine to the United Nations Security Council.

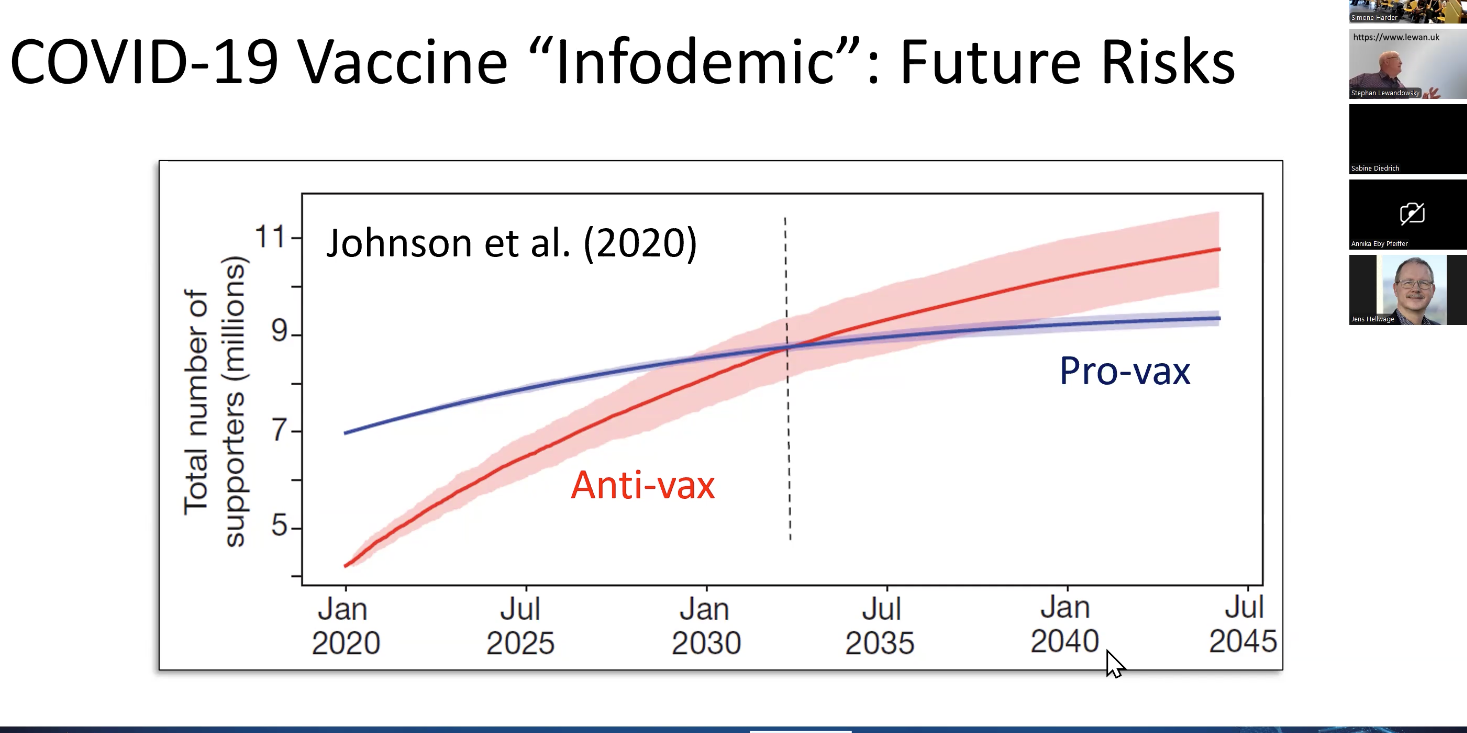

Proponents of truth still outnumber their opponents on Facebook. But because the future is malleable — and algorithms learn quickly — a different trend is already taking shape on the world’s largest social network. ⬇️

The tipping point is not far off: Facebook is following in the footsteps of X.

Since changing its content policy, Facebook has largely stopped moderating posts — meaning falsehoods are likely to spread even faster across the network. „So we have a problem“ says Stephan Lewandowsky.

During the pandemic, he was part of a team that worked with the Canadian government to model what a society without disinformation might look like. The researchers wanted to understand the impact of misinformation on public health and the economy. Their conclusion: in Canada alone, 3,000 fewer people would have died and tens of thousands fewer would have been hospitalized. The estimated economic savings: 300 million dollars.

But the damage is not just economic — it divides societies and corrodes democracy. Even before the pandemic, Russian-backed bots, “content polluters,” and trolls had amplified the vaccine debate, supporting both pro- and anti-vaccine narratives with highly charged political messages designed to sow discord. Their goal? To undermine public understanding of vaccination while exploiting and deepening existing social divides.

Disinformation corrodes democracy.

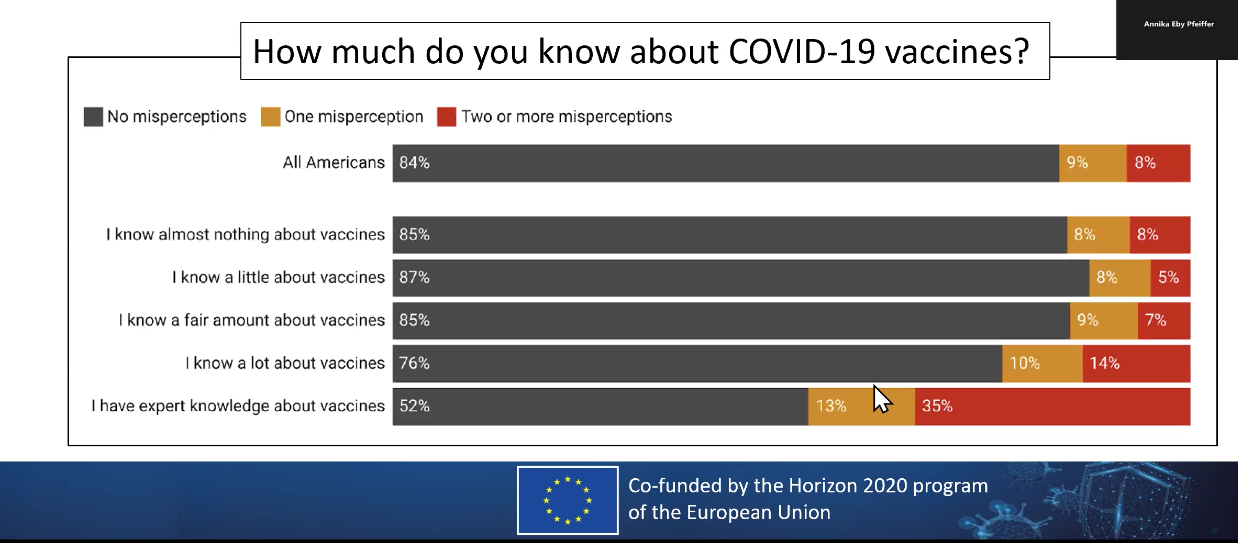

Disinformation thrives where information is scarce. Ironically, it is often the spreaders of misinformation who claim to be particularly well-informed.

Lewandowsky cites a 2022 U.S. survey on knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines: 85% of respondents said they knew little or nothing about vaccines — a good sign, as it also meant they were less exposed to misinformation. But almost half of those who called themselves “vaccine experts” shared false information. „The people who need to be informed the most, are the ones who think „I know it all“.

A weekend on the internet turns people into experts. Or so they think.

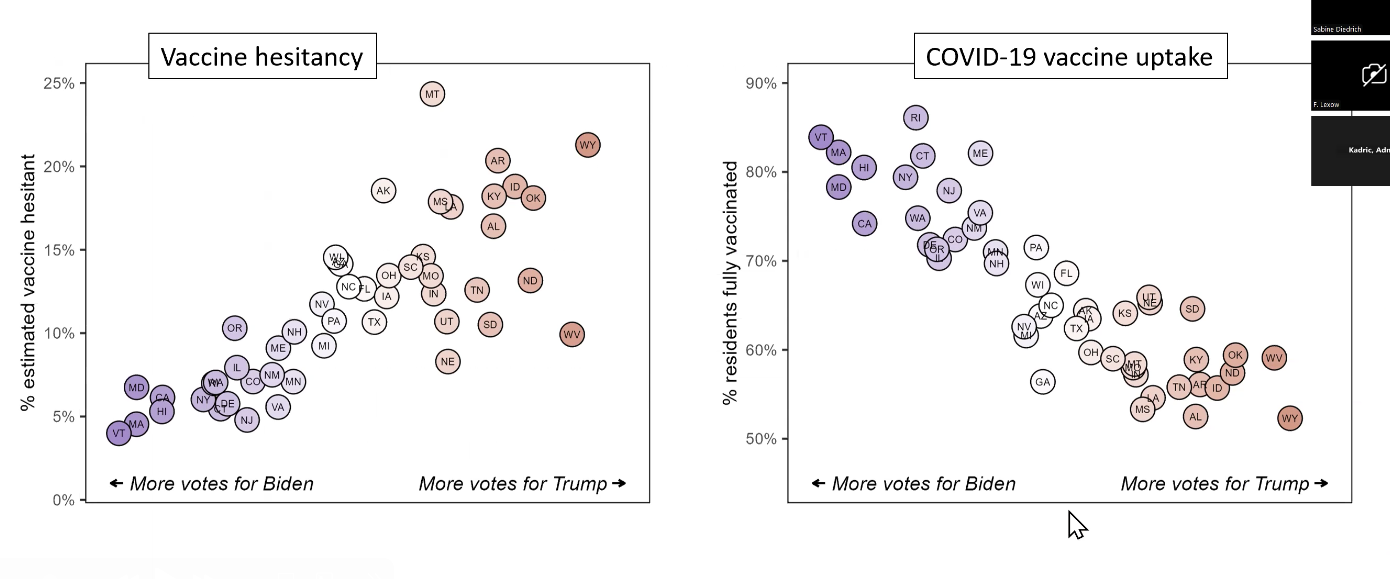

Not exactly surprising: The majority of people who refuse vaccinations vote for Donald Trump, while those who get vaccinated tend to vote for Joe Biden. „The more trumpier the state, the greater the vaccine hesitancy" says Lewandowsky. The finding is no coincidence, he adds, and countless studies confirm the same pattern. “The more people watching Fox News, the less likely they are to get vaccinated.”

California vaccinates and votes for Biden. Wyoming stays unvaccinated and is for Trump.

But if you can’t convince people with facts, what do you do? Give up? Use force? Just watch soccer? “Be empathetic,” says Lewandowsky.

“Be empathetic,” says Lewandowsky. He doesn’t just want to conduct research — he also wants to bring about change. That’s why he wrote a guidebook years ago: “The Debunking Handbook.” It has been translated into several languages; the German version is called „Widerlegen, aber richtig“ (Debunking, but doing it right).

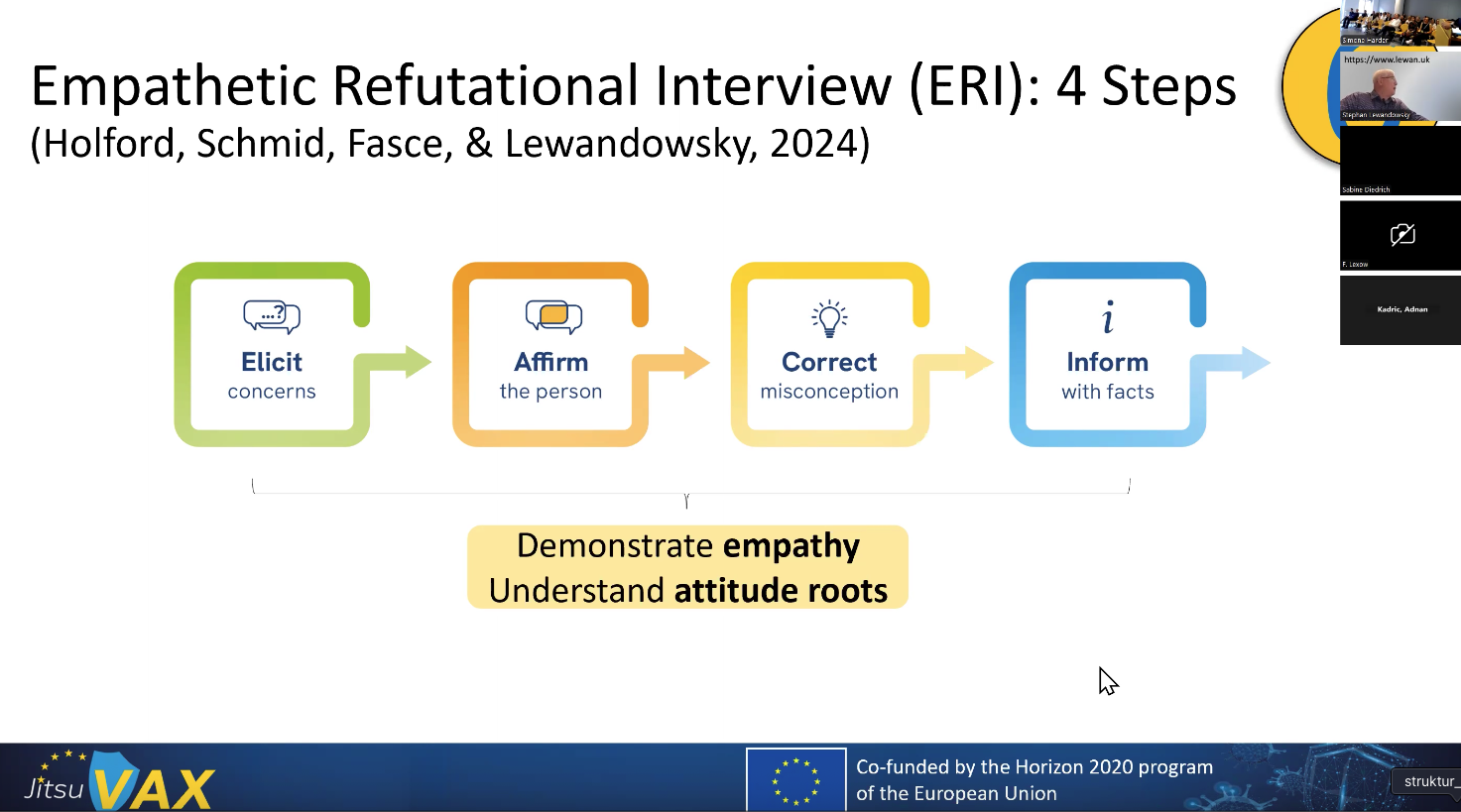

ERI is the name Lewandowsky gives to the method he and his team have developed. Kurt Beck called it: “Close to the people.”

Build trust first. Spend time with people, ask about their concerns, and address them. Talk about everyday life, your children, and confirm some things — not everything, of course. Acknowledge real issues, like conspiracies that did happen, for example the diesel scandal at VW.

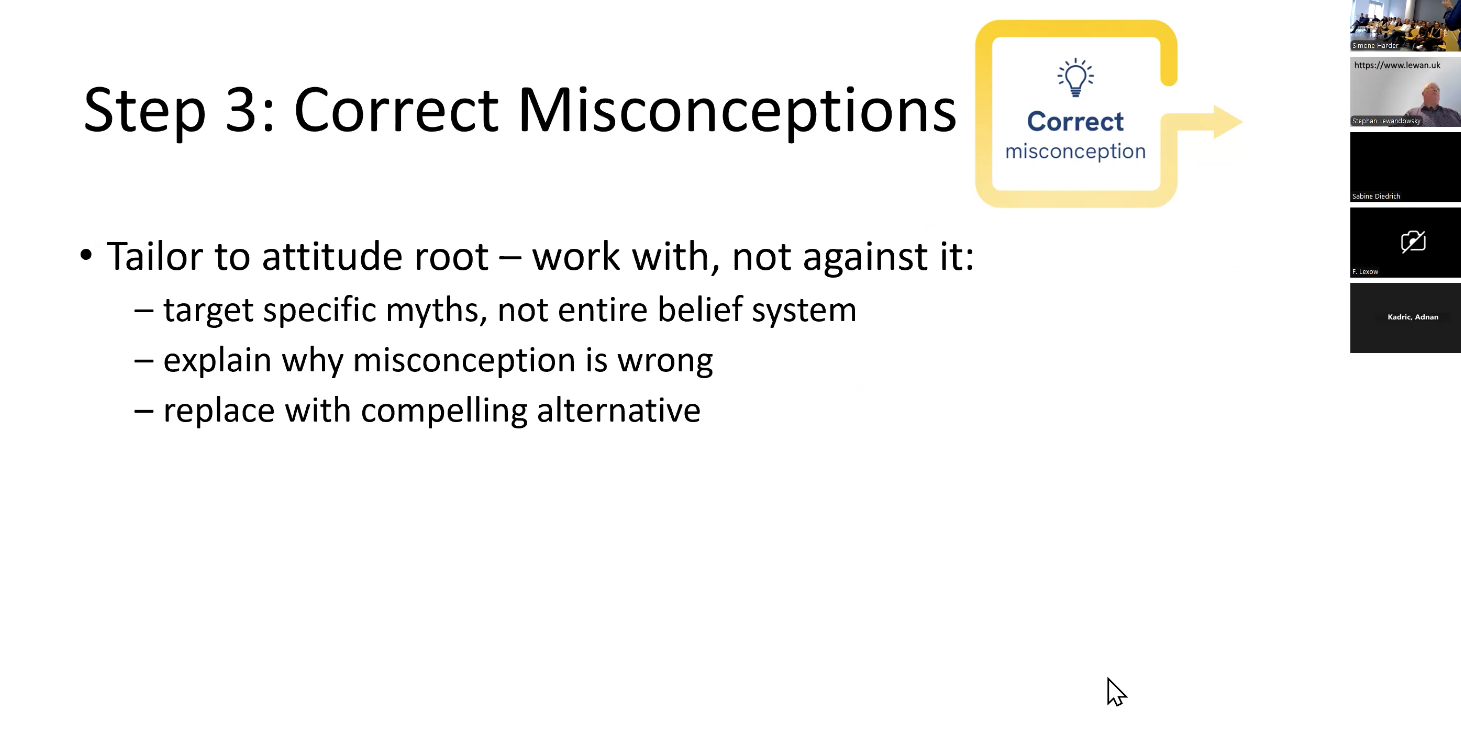

„Confirming the person,” says Lewandowsky — that’s what it’s all about. Shared experiences help: drink a beer together, joke about the ’80s, establish common ground. Once trust is established, you can gently correct misconceptions — no, there are no razor blades in the vaccine, there is no Great Reset. Open another beer, and now you can even discuss more sensitive topics like Bill Gates — you’re meeting people where they are and creating a space for conversation.

Change the subject, then return. Discuss everyday frustrations, like Bayern Munich always winning the German championship, or personal memories. Gradually shift to vaccines — but never act like a know-it-all. Even if you know the details perfectly, phrases like “I don’t think so” or „I believe“ work far better than overwhelming someone with the minutiae of a virus mutation in a distant district. Kurt Beck, former SPD Minister President of Rhineland-Palatinate, summarized it simply without a study: “Nah bei den Leit” — close to the people.

Beliefs are part of peoples’ identities

Lewandowsky tested this approach in Romania, a country with high vaccine resistance typical of former Eastern Bloc nations. “Romania is a tough target,” he says. Doctors, nurses, and aid workers are key, and the most trusted sources of information for most people, even now. It’s labor-intensive and slow, but it often works.

What doesn’t work: a professor from a big city presenting facts, a politician from the government making suggestions. Their statements are perceived as elitist and untrustworthy. Nor does it work to lecture, disparage populations, or act as if someone else will handle the work.

Combating disinformation is hard, grassroots work, requiring engagement at the local level — sports clubs, volunteer fire departments, reading to children, maintaining trails, playing boules with the elderly. “Saving democracy is micromanagement,” Lewandowsky says.

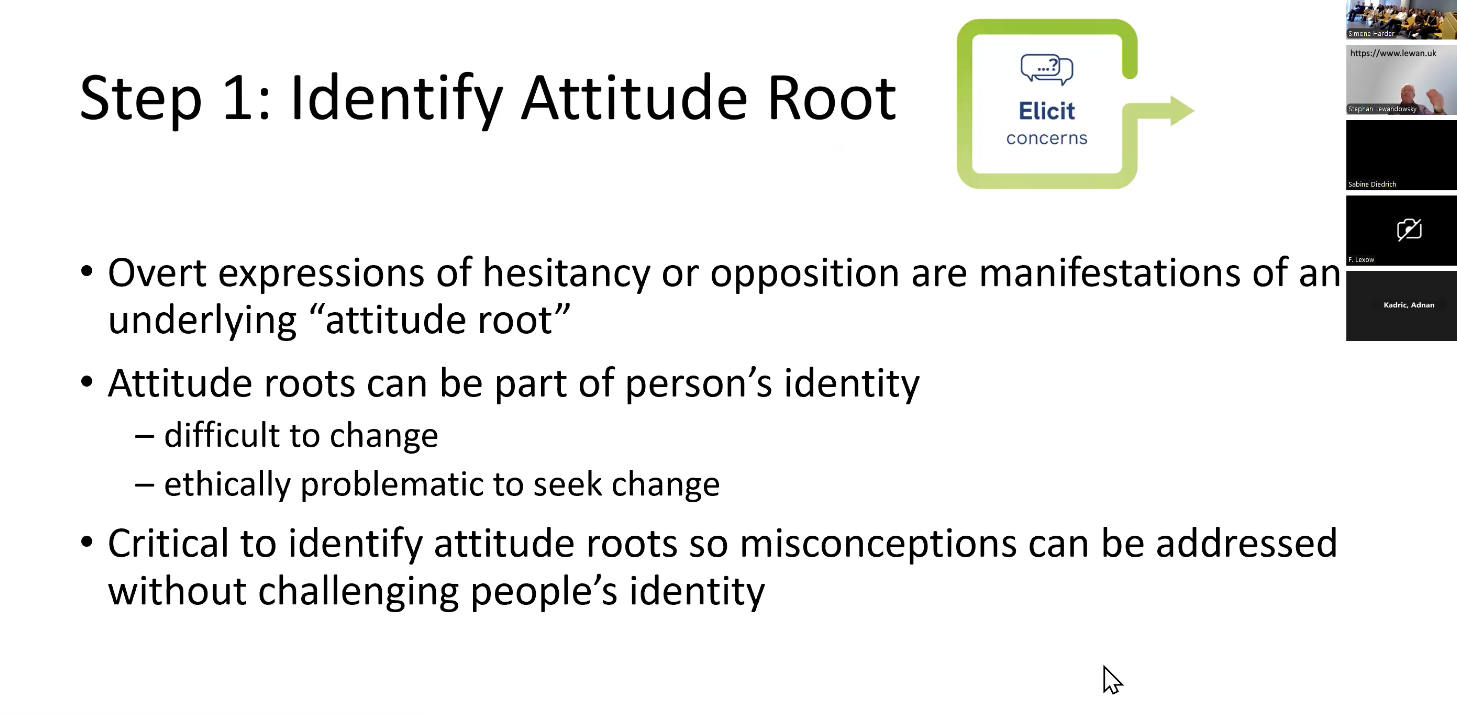

Empathy matters because beliefs are identity. Political or cultural beliefs are often deeply tied to who someone is. Trying to convince them otherwise can feel like an attack on their identity, producing resistance.

To put it another way: a conversation with Markus Söder about wind energy routes is far more productive if you eat a bratwurst while you’re at it, rather than attempting to make a tofu burger appealing.

When disgruntled citizens oppose something—vaccinations, climate change, heating—it is often rooted in something else.

Understanding the roots of attitudes, Lewandowsky points out that there are patterns in the origins of people’s attitudes. Two stand out in particular: Fear/phobia, and distrust. When it comes to vaccination, for example, virtually all arguments can be traced back to one of these two roots. Recognizing this helps with counterarguments, because it clarifies where someone’s hesitancy or resistance is coming from — especially when you ask why they feel mistrustful or fearful.

This means that if someone is afraid of side effects, it’s better not to talk about the government.

Once trust is built, small agreements are made, and the source of concern is understood, you can begin dismantling existing beliefs. By agreeing on a side issue, you avoid challenging someone’s entire worldview — their identity — and instead question a single conviction in a concrete, non-threatening way.

Dissent should not call all beliefs into question at once.

If you don’t stigmatize people, don’t pigeonhole them, but engage with them, they are surprisingly open to reconsidering their beliefs. “This is not just wishful thinking,” says Lewandowsky.

A study he conducted last year in the UK with 4,225 vaccine-critical participants found that over two-thirds did not believe medical staff when facts were presented alone. However, when the same facts were embedded in empathetic affirmation of the participants’ identity, only slightly more than a third remained opposed.

Can empathy work beyond vaccines?

What about climate change deniers or nationalists? Can this method be generalized to other areas of disinformation?

Yes. Lewandowsky’s team ran two further experiments on topics unrelated to medicine, including cultural conflicts and political issues, such as gender debates and youth voting behavior in the UK. “You can take any topic where people are passionate, polarized, and yelling at each other — but through the empathetic approach, you can move the needle,” says Lewandowsky.

The method is simple in principle: Listen and understand where people are coming from, find common ground and agree on a side issue — their fear, mistrust, or other identity-linked concern, and stand by your opinion: be friendly, but firm. Empathy comes first. Facts come later. The key is to meet people where they are, without fighting or attacking their identity.

OWhether someone is a vaccine skeptic or a climate change denier, it is always worth trying to find common ground. This approach can ultimately help convince people in specific areas — even though it’s difficult.

This approach assumes that people are willing to engage and do not shy away from conversation. In the closed online world of networks, meaningful exchange is often more difficult than at an offline gathering, like a folk festival.

But the pattern remains the same: simply presenting facts is pointless. Facts alone often attack people’s identity and provoke backlash. Those who acknowledge concerns without condemning them and work with the argument are more likely to reach people — because their identity is no longer threatened. It is hard work. It is resource-intensive. It does not happen automatically.

But it is possible.

Effort can make a difference.