"Ten times more cases"

Some children develop a severe inflammatory reaction after a mild coronavirus infection—known as Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), or pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (PIMS) . For a long time, the underlying cause remained unclear.

A team led by Dr. Mir-Farzin Mashreghi from Berlin has solved the mystery.

MIS-C/PIMS is a rare but severe condition that can develop weeks after a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents. It results from an overactivation of the immune system, resembling other hyperinflammatory diseases characterized by severe, feverish immune reactions.

In the search for what triggers MIS-C, a team led by Dr. Mir-Farzin Mashreghi, Deputy Scientific Director of the German Center for Rheumatism Research (DRFZ) in Berlin, identified a connection with another virus: the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

EBV, a herpes virus, infects about 90% of people worldwide and is best known as the cause of glandular fever (also known as infectious mononucleosis or Mono). Most infections are mild or unnoticed, though some can cause flu-like symptoms and require extended recovery. Dr. Mashreghi is the lead author of the study “TGFβ links EBV to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children”, published in Nature in March

During the coronavirus pandemic, around 1,000 children in Germany alone fell ill with MIS-C. However, hyperinflammatory diseases already existed before that. What was unusual about the new cases?

At first, MIS-C appeared to be a normal, severe inflammatory response, similar to those seen in other hyperinflammatory diseases. But then such rare cases suddenly became more frequent in children – four to eight times more frequent than usual. Although MIS-C is rare overall, all affected children must be admitted to intensive care. Without timely treatment, the disease can be fatal, even in previously healthy children.

What could explain this phenomenon?

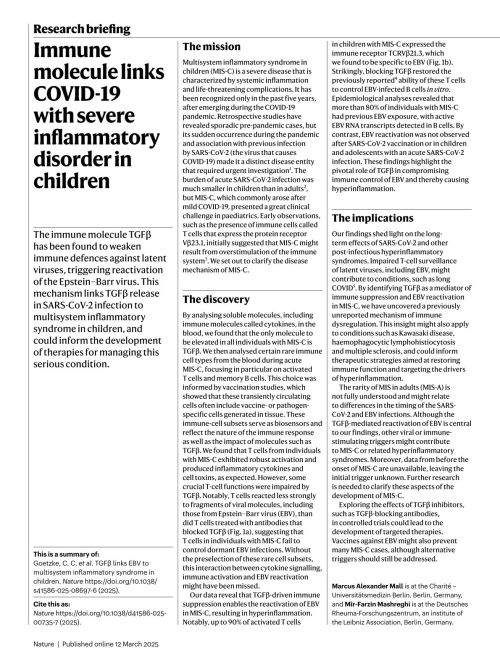

To understand why MIS-C occurs, the researchers measured 46 signaling molecules in the blood serum of affected children. In all cases, TGFβ levels were noticeably elevated. Previous studies in 2021 had shown that TGFβ also plays a role in severe COVID-19 in adults, appearing at unusual times.

What is TGFβ?

This messenger substance is normally released when the immune system has successfully fought off a virus, helping the body return to immune balance. In severely ill COVID-19 patients— and in children with MIS-C—TGFβ is produced far too early, while the virus is still present. This interferes with the immune system’s ability to eliminiate infected cells, contributing to the hyperinflammatory response.

MIS-C/PIMS: A Bigger Problem Than Initially Thought

Were the affected children also seriously ill from the initial infection?

Some didn't even notice the SARS-CoV2 infection. In most cases, it was mild. But four to six weeks later, these children suddenly developed this systemic inflammatory response. At first glance, the inflammation has nothing to do with SARS-CoV-2. After all, the infection is gone and SARS-CoV2 is no longer detectable.

But, is there a connection?

Researchers examined activated immune cells, which act as biosensors in the blood and normally appear only briefly during an infection, signaling that the immune system is responding properly. In children with MIS-C/PIMS, however, these activated cells remained detectable in the blood continuously. Through gene expression analysis, the team demonstrated that the messenger substance TGFβ affects these activated cells. This immune-suppressing effect of TGFβ provides the mechanistic link between MIS-C/PIMS in children and severe COVID-19 in adults, explaining why the immune system becomes overactive even after the virus has disappeared.

For their investigation, the researchers examined 145 children and adolescents between the ages of 2 and 18 who had been treated for PIMS between 2021 and 2023 at Charité in Berlin and hospitals in France, Italy, Turkey, and Chile. For comparison, the team also studied 105 children who had experienced a SARS-CoV-2 infection but did not develop PIMS, providing a baseline to identify what differentiates affected children from those with mild or asymptomatic infections.

Could Immune Suppression Give Other Viruses a Chance?

The researchers investigated whether overactivation of TGFβ — which suppresses the immune system — might allow other viruses to multiply more easily.

To understand this, it helps to know the two main types of immune cells involved: B cells have antibodies that the virus recognizes, and T cells have corresponding receptors that are specific to certain viral proteins, meaning they are specialized cells that use their keys to recognize different viruses on the surface.

So the lock-and-key principle recognizes specific structures?

That is correct. The research team took the activated T cells from the sick children, and use sequencing technology to try to identify the “keys” i.e., their receptors, based on their sequences. These sequences were then compared with other sequences that were known to recognize specific protein structures of distinct pathogens, like the structures of the Epstein-Barr virus, EBV.

There is an immune response to a herpes virus that 95% of all adults have in their bodies

And, what is a good fit?

Researchers discovered that the T cells of children with MIS-C are similar to those that recognize the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). This suggests that children who develop this inflammatory response have a specific immune “key”, similar to EBV-specific T cells found in healthy individuals. Which is uncommon, as there appears to be an immune response to a herpes virus in these MIS-C children to a herpes virus that 95% of all adults have in their bodies.

But, do the children have this disease?

In the vast majority of people, EBV is dormant. However, for children, the story is different. Only half of all children up to teenage age have had contact with the virus. The next step of the research, was therefore to clarify whether the examined children had already had contact with EBV.

How is that done?

Previous infections can be measured by looking for antibodies in the bloodstream. And 80% of the children who were ill had EBV antibodies. So if a child is already infected with EBV, they are more likely to develop MIS-C. That is one of the two risk factors.

What is the second risk factor?

SARS-CoV-2 infections. These lead to higher TGFβ-levels in these children. The messenger substance TGFβ then prevents the immune cells from keeping EBV in check. The infected cells then produce more and more EBV without the immune system being able to fight them. However, the innate immune system does respond to the viruses by producing pro-inflammatory messenger substances. This ultimately culminates in an extreme inflammatory reaction that can damage organs and be potentially fatal.

So far, treatment for MIS-C has focused on slowing down the immune system's excessive response by administering cortisone.

There are antibodies that block TGFβ, because this is a mechanism that tumor cells also use to evade the immune system. Of course, it’s not possible to simply block a molecule in children that you’ve just recently discovered. For that, much more research needs to be done. Therefore, reserachers worked with serum. And all in vitro.

That’s all well and good, but MIS-C and PIMS are both very rare. Why should I care if I don’t have the disease?

Because this research highlights that EBV is not harmless. And almost all of us have the virus in our bodies—95% of people. That should be of interest to everyone. An EBV infection can trigger inflammation of the brain, can lead to development of multiple sclerosis, and is also suspected to trigger or exacerbate other autoimmune diseases, which damage various organs.

So ideally, a vaccine against EBV is needed.

This research highlights a need for this vaccine. However, the findings could also be helpful for long-COVID, as there are indications that the reactivation of dormant viruses plays a role there as well. Perhaps there are parallels to the processes involved in MIS-C, in which case TGFβ-inhibitors would be potential candidates for therapy against long COVID.