Because I choose to.

From Doubt to Discovery: Understanding Science’s Credibility

Science, is like Neo from The Matrix:

Protecting Us in Ways We Don’t Expect

Many realities, one truth: science still has our trust.

via TNT, TM & © Warner Bros.

Many realities, one truth: science still has our trust. You don't need to delve into conspiracy theories or follow Keanu Reeves as Neo in The Matrix to realize that people inhabit different realities. Just switch on a talk show or scroll through your social media feed — nonsensical content is everywhere. Add a skeptical relative at a birthday party and suddenly the world feels full of misinformation.

Among the most persistent doomsday stories is the idea that scientists have a credibility problem. Nobody trusts research anymore. Gut feeling and 'common sense' are supposedly the real currency, while experts are dismissed as speaking from ivory towers. Everyone 'knows' that.

Except it isn't true.

In fact, scientists remain among the most trusted voices in society. A global study led by Markus Huff and more than 200 co-authors called, “Trust in scientists and their role in society across 68 countries” makes this crystal clear: trust in scientists is consistently and globally high.

Huff is the Associate Director of the IWM (Leibniz Institute for Media Knowledge) and a Professor of Applied Cognitive Psychology at Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen. The IWM is one of 41 institutes collaborating in the Leibniz Pandemic Preparedness Lab. When asked about the public’s relationship with science, Huff has one hopeful result: “Trust in science is moderately high.”

Markus Huff is the Associate Director of the Leibniz Institute for Media Knowledge in Tübingen

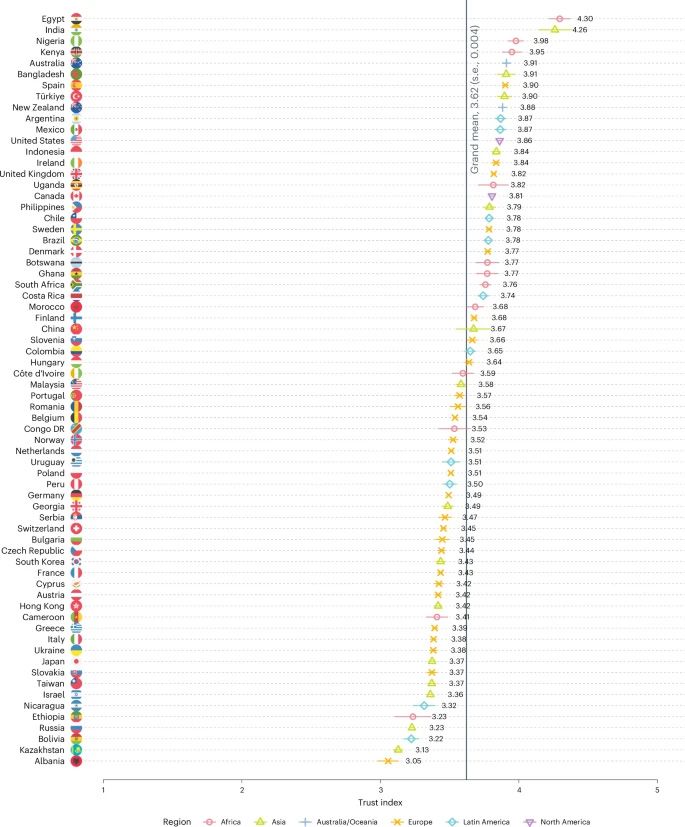

The word “moderate” might not sound particularly enthusiastic — it feels cautious, maybe even a bit bleak. But the numbers tell a different story: 57% of people surveyed believe that scientists are honest, and 56% believe that scientists care about the well-being of others. And these aren’t just local figures — this is worldwide. The study covers public opinion in 68 countries, representing nearly 80% of the global population. “What makes this study special is its size and international scope,” explains Huff. “No country shows low overall trust in scientists. Across the globe, people see scientists as highly competent.” In other words: not a single society is hostile to science.

And isn’t that something worth celebrating?

Spain stands out as the only European country to rank among the top 10 nations with the highest trust in science.

Public trust in science might be stronger than many assume.

But the picture varies dramatically around the world. Egypt leads globally in scientific trust, follwed closely by India and Nigeria. The United States, despite widespread criticism, ranks 12th — well above China, which sits in the middle of the pack. Notably, only one European country, Spain (8th place) cracks the top ten. Europe’s relationship with science appears to be more complicated. Germany, often viewed as a beacon of rational policy-making, ranks surprisingly low in the lower midfield, nestled between Peru, Georgia, and Serbia. However, the Germans still outperformed several of its neighbors: Switzerland, France, and Austria all rank lower.

The data confirms what many have observed anecdotally:

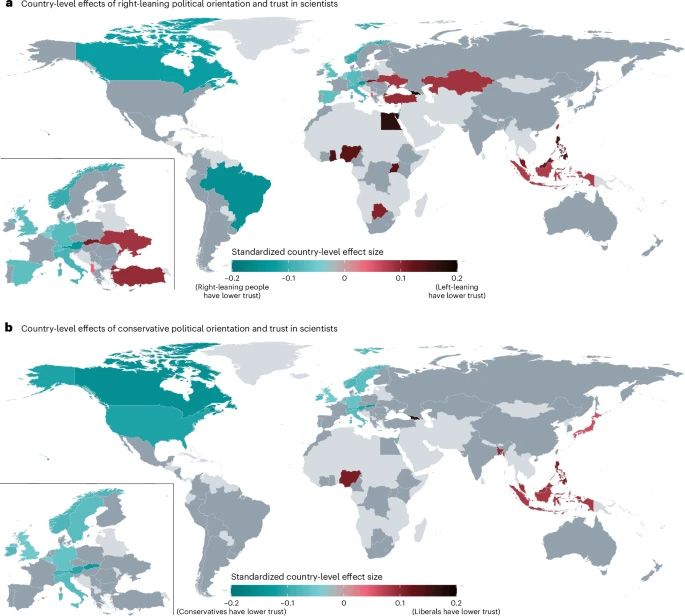

Uneducated, conservative men in rural areas show the lowest trust in science. However, this pattern generally applies only to the US and Europe. Expanding the view globally reveals one striking finding. Political orientation doesn’t universally predict scientific trust. In fact, in many Asian and African countries, the relationship actually reverses — the more politically conservative the population, the higher their trust in scientists.

This geographic variation suggests that scientific trust isn’t simply about education or political ideology, but reflects deeper cultural and institutional factors that vary significantly across regions.

The political divide around science isn’t universal — its manufactured. In some countries, right-wing parties have deliberately fostered skepticism toward scientists, while elsewhere left-wing movements lead the charge in skepticism towards science. However, this reveals something hopeful: if distrust can be learned, it can also be unlearned.

Perhaps most importantly, Huff’s research also challenges a common assumption about education and science skepticism: that less educated people automatically reject science. This is simply not the case. While people who are less education often distrust scientific institutions, they generally maintain faith in scientific methods.

While this distinction may seem trivial, it matters enormously for rebuilding trust. Because the problem is not that people have abandoned rational thinking or lost respect for evidence-based approaches. The problem is that they have lost confidence in the organizations and authorities that communicate scientific findings. Understanding this difference opens pathways for reconnection that focus on transparency, accountability, and rebuilding institutional credibility, rather than simply providing more education.

When Education Isn’t Everything

Across most countries, education status shows no correlation with scientific trust. This means highly educated individuals can be just as likely to spread misinformation and undermine trust in health authorities like the CDC or Germany’s Robert Koch Institute. And unfortunately, they often do.

“Some people politically exploit the narrative that ‘no one cares about science anymore,’” explains Huff. “But it’s not really about science — it’s about the institutions behind it.” This is the distinction that proves to be crucial for understanding how scientific skepticism spreads, even amount those who should know better.

Prejudices Confirmed and Challenged

The data from Huff’s study validates some expected patterns, while overturning others. For example, Russia ranks near the bottom in fourth-to-last place, joined by several former Soviet republics. In the United States, religious belief does correlate with research distrust, fitting familiar cultural narratives.

However, most Muslims worldwide see no conflict between science and religion — in fact, it’s quite the opposite. Religious faith often strengthens rather than weakens scientific trust. Three Muslim nations rank in the global top ten, alongside four Christian countries and Nigeria (roughly half Muslim, and half Christian) in third place.

A Reason for Hope

Perhaps the most encouraging message from this study is this: the overall picture of scientific trust looks brighter than media coverage suggests. “Trust in science is surprisingly high,” Huff concludes. “And it’s apparently difficult to shake — that’s good news.”

Politische Einstellung im Verhältnis zur jeweiligen Glaubwürdigkeit von Wissenschaft.

However, it is important to note that just because the global trust in science is high does not mean that science operates without serious problems. The root of many internal problems lies in academia’s “publish or perish” culture. Researchers face relentless pressure to publish early and in specialized journals to build their reputations and secure their careers. This system, designated to encourage productivity, increasingly undermines the very quality it was meant to promote. And the consequences reach far beyond individual academic careers — they threaten the foundation of public trust in science.

Estimates suggest that roughly 2% of the six million research papers submitted annually are fraudulent. While this might sound small, it translates to hundreds of thousands of fake studies flooding the academic literature each year. And advancing artificial intelligence only worsens the situation. And the field most drastically affected by this? Medicine.

The overarching goal? To destroy the institutions

Entire industries are now producing fraudulent research papers, with many originating from Russia and China. Entire industries are behind the wave of fake scientific papers — many originating from Russia and China. The aim is clear. To erode trust and destabilize societies. And often, the foreign policy interests of certain states align with the domestic agendas of populist groups.

Populism, after all, has long targeted science. When a society loses its shared factual foundation, common ground disappears. Division grows, and with it, opportunities to seize or secure power. Huff’s study also supports this observation, showing that those who favor hierarchy enhancement are less likely to trust scientists. Attacks on universities, can thus be seen as attempts to weaken the very institutions capable of challenging existing social hierarchies.

This dynamic isn’t confined to one place. In November 2021, before he became senator from Ohio or Vice President of the United States, J.D. Vance delivered a keynote at the National Conservatism Conference in Orlando. Its title? “The Universities are the Enemy.”

Professors and researchers make the perfect targets. Why? Their work is often invisible to outsiders. Most people don’t really understand how science works, and their research often seems so specialized that it appears irrelevant to everyday life. This all together makes it all too easy to caricature scientists as detached from reality.

Researchers also lack defense. Unlike celebrities, they have no social media armies to defend them. Without Swifties or other superfans, they lack reach. As a result, the term “science” is frequently politicized and turned into a catch-all synonym for whatever someone disagrees with — be it liberalism, immigration, bureacracy, or certain social values. After all, science itself isn’t able to functions without those very frameworks. And while institutions cannot be easily personififed, scientists can. That makes them tangible, visible — and therefore, vulnerable.

Yet, despite this vulnerability, trust remains strong. As shown in, “Trust in scientists and their role in society across 68 countries” scientists still enjoy relatively high credibiility and largely positive reputations worldwide. That resilience speaks volumes — not only about their strength, but also about the value of their work.

Attacks on scientists do not mean that trust in science has vanished. In fact, they reveal just how seriously opponents take science. Efforts to undermine credibility, such as casting doubt, are not only directed at science itself. They strike at something deeper: the shared foundation of facts and understanding that holds society together.

Popular science often fuels an uncessary clash between common sense and academic elites. With “the commoners”standing on one side of the imaginary line, and professors — portrayed as ivory-tower gender studies experts who are disconnected from real life problems — on the other. In this context, “common sense” more often than not means that those with little knowledge of a subject feel empowered to pass judgment on it.

“Without trust in science, research remains ineffective,” says Huff. Yet his study reveals that politicians could be placing more trust in the actual voters. “Policymakers must recognize that there is already a high level of trust in science.” And political decisions can — and should — rest on science as a matter of principle. What helps? “Crystal-clear communication,” Huff emphasizes.

There’s a reason disinformation so often dresses itself in scientific language and sweeping claims. It exploits trust in order to confuse. Its aim isn’t to convince, but to plant seeds of doubt. Vaccination is a textbook case. The evidence is overwhelming: vaccines save lives, prevent disease, and are produced under some of the strictest regulations of any industry. And yet, in parts of society, vaccination remains contested. The myth that vaccines cause autism has been debunked countless times — but like the Fast & Furious franchise, measles keeps coming back with another unwanted sequel.

On social media, disinformation has a built-in edge. It stirs emotion, fuels interaction, and is amplified by algorithms. Add in the swarms of Russian and Chinese bots seeking destabilization, and fake news can start to blur into fake reality. And when perceived reality shifts, it doesn’t stay harmless — it seeps into politics, hardening into “real” reality. (Have we arrived at The Matrix?)

But it’s not that simple. Because here’s the good news: people generally do trust science.

And so science, in a way, is like Neo. Beaten down, underestimated, sometimes seemingly defeated — but never giving up. Even when the odds look overwhelming.

As Agent Smith sneers: “Why, Mr. Anderson? Why keep fighting? Why persist?”

Neo’s answer is simple: “Because I choose to.” And Huff’s study echoes this resilience: with 54% of respondents saying science should communicate more with the public. In other words? Just. Keep. Going.