The WHO Pandemic Agreement:

Still A Long Road Ahead

© Philipp Kohlhöfer

While the new pandemic agreement signed by the World Health Organization (WHO) is a step forward, it’s far from a finished solution. Key details — like the specific measures in the treaty’s appendix — are still being worked out. Plus, with confirmation from all 194 WHO member countries still pending, it could take years before the treaty is ratified by the required 60 countries. So, while the treaty adopted in May 2025 is a positive development, there’s still a long road ahead.

In a different time, a 31-page document that leaves so many questions unanswered might have been met with disappointment. But these are not ordinary times. In the midst of rising nationalism and political tensions, this agreement shows that multilateralism in global health is still alive, even if it’s facing strong headwinds. For example, the United States, once the WHO's largest donor, hasn’t been part of the negotiations since late 2024, following a decision by the Trump administration to withdraw. That withdrawal will officially take effect in January 2026, marking a significant shift in global health leadership.

Even with its imperfections, this agreement is essential. Experts like those at the Harvard School of Public Health have emphasized that the question isn't "if" the next pandemic will strike, but "when." The global vaccine alliance, CEPI, places the chance of a new pandemic at 38%. And the reasons are clear: humans are increasingly encroaching on wildlife habitats, creating new opportunities for diseases to jump from animals to humans. Climate change is driving the spread of pathogens, and the rising movement of people around the world means viruses can travel faster than ever before. The work is far from over, but this treaty is a crucial first step in protecting global health. We have no choice but to act now, because the next pandemic could be just around the corner.

The One Health Concept is Pandemic Prevention

“A One Health approach is fundamental to effective pandemic prevention,” says Michael Stolpe, head of the Global Health Economics project at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) and co-spokesperson for the Leibniz Lab Pandemic Preparedness. Understanding and preventing future pandemics requires a comprehensive view of the complex interactions between humans, animals, and the environment. Only by studying changes in natural ecosystems — and how human activity affects them — can we identify the conditions that increase the risk of new pathogens emerging.Stolpe explains: “We need to understand how shifts in the relationship between humans and wild or domestic animals increase the likelihood that pathogens will jump from animals to humans. After all, to trigger the next pandemic, novel pathogens must first emerge that our immune systems have never encountered.”

However, Stolpe points out that not all governments have embraced the One Health approach. “In the negotiations over the pandemic agreement, some countries resisted stronger emphasis on One Health—partly because of political sensitivities surrounding the origin of SARS-CoV-2.n.Those favoring the laboratory accident theory often wish to avoid expensive investments in biodiversity protection and ecosystem conservation, preferring instead to focus on agricultural expansion and food security.”

“No country can defeat a pandemic on its own,” says Michael Stolpe.

The Pandemic Agreement, developed in response to COVID-19, aims to strengthen global preparedness and cooperation. But its negotiation proved challenging. Widespread conspiracy theories and political tensions forced negotiators to repeatedly clarify that national sovereignty would not be compromised.

“It was very complicated,” recalls one participant, who spoke on condition of anonymity. Germany and the European Union, he adds, played a key role in pushing for a strong, balanced agreement. While the EU is not the only actor striving to uphold a rules-based international order, it currently stands out as one of its most active defenders — alongside countries such as India.

It’s Complicated

Reaching agreement on the pandemic treaty was far from simple. Tensions and mistrust shaped the negotiations, especially between Western and African countries. On one hand, many African governments have had difficult experiences with Western health policies in the past — so a certain skepticism toward international initiatives is understandable. On the other hand, Russia has deliberately fueled conspiracy narratives across Africa to advance its own geopolitical influence. A study by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, published about a year and a half ago, analyzed the sources of disinformation campaigns on the continent. Of 200 documented campaigns, 80 were clearly linked to Russian actors. This is not a new phenomenon: conspiracy theories have been part of Russian foreign policy since at least the early 2000s, with more than 125,000 academic entries on the topic listed on Google Scholar.

Despite these political headwinds, Russia ultimately agreed to the pandemic treaty.

Dr. Stefan Kroll, from the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) – Leibniz Institute for Peace and Conflict Research, views this as a notable achievement in today’s fractured geopolitical climate. He emphasizes that the treaty’s commitment to prevention and equitable management of future health crises is of particular importance: “During the coronavirus pandemic, we saw clear shortcomings in vaccine equity and international solidarity,” says Kroll. “Whether the current treaty can address these issues remains to be seen—much will depend on how its provisions are implemented.” PRIF is among the institutes contributing to the ‘Pandemic Management’ research focus at the Leibniz Lab Pandemic Preparedness.

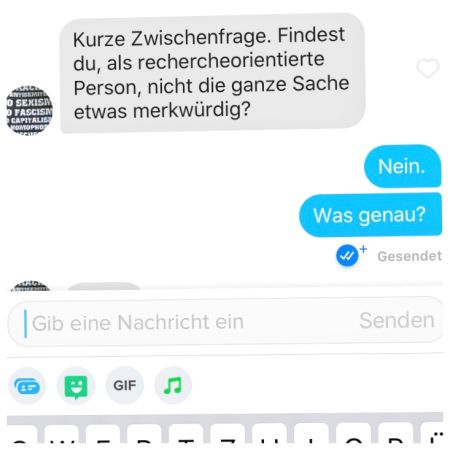

From COVID to the pandemic treaty, conspiracy theories persist. They spread fast — both online, and in politics, not just on Tinder.

It took more than three years to negotiate the 35 articles of the Pandemic Agreement. Talks began in December 2021 — shortly after it became evident that the European-led COVAX initiative had fallen short of its goal. Designed to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for low- and middle-income countries, COVAX was undermined when many high-income nations secured the majority of available doses and medical supplies for themselves. As a result, very little reached poorer countries. The new agreement seeks to prevent such inequities from happening again. But, will it succeed?

“The planned Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System (PABS), outlined in the yet-to-be-finalized annex, will be crucial.” Explains Michael Stolpe. Under the proposed PABS framework, DNA sequences of newly identified pathogens would be shared with participating pharmaceutical companies. This would allow them to accelerate the development of vaccines and treatments. In return, companies would donate ten percent of their products to the World Health Organization (WHO) and offer another 10% at reduced prices. The WHO would then distribute to low- and middle-income countries. In this way, the system aims to link faster vaccine development with greater global equity — a lesson learned from the shortcomings of the COVID-19 response.

Das soll der Vertrag regeln:

- Prevention: Countries will commit to strengthening their public health systems and improving animal health surveillance. The goal will be to detect disease outbreaks early and contain them before they can spread.

- Supply Chains: All countries should have reliable access to protective equipment, medicines, and vaccines. In future crises, healthcare workers are to be prioritized first and foremost for distribution.

- Technology Transfer: Pharmaceutical companies will be encouraged to share their expertise so that vaccines and medicines can also be produced in other regions of the world.

- Research and Development: Genetic information from newly identified pathogens will be made available to accelerate the development of vaccines and treatments. In return, pharmaceutical companies are expected to donate 10% of their production to the WHO and offer another 10% at reduced prices. The WHO will distribute these supplies to low- and middle-income countries. The specific details of this PABS are still being negotiated.

The Annex Still Needs to Be Negotiated

One key element of the treaty, the annex detailing the PABS, has yet to be finalized. Participation by pharmaceutical companies is currently planned to be voluntary, raising questions about how many doses of newly developed vaccines they would actually provide to the WHO free of charge or at reduced prices in the event of a future pandemic.

“If the annex is not finalized, the entire pandemic agreement could ultimately fail,”, warns Michael Stolpe. “Moreover, many of the 35 articles are written in rather general terms, leaving room for differing interpretations.”

According to Stolpe, this lack of precision reflects the need to balance a wide range of national interests and political perspectives. However, he adds, if disputes arise during the implementation of preventive measures or in the aftermath of a new outbreak, the WHO currently has no effective mechanisms to enforce compliance or sanction violations of the agreement. Despite this limited authority, conspiracy theories continue to circulate—claiming that the agreement would turn the WHO into an all-powerful global government capable of closing schools anywhere in the world. That notion is, of course, entirely unfounded.

As Always, There Are Conspiracy Theories

The pandemic agreement applies only to those countries that choose to ratify it, and only after at least 60 WHO member states have done so. In any case, all participating countries retain full national sovereignty. The WHO cannot dictate what measures governments must take, it can only issue recommendations. Many of the commitments made under the treaty are explicitly tied to national legal frameworks, using phrases such as “in accordance with national laws” or “by mutual agreement.”

Even if a country were to violate the treaty — which would ultimately harm its own ability to respond to future crises — there are no sanctions. The WHO is not a police authority, it has neither the mandate nor the power to enforce compliance.

In future, healthcare workers will be better protected and receive faster care.

As part of the pandemic treaty, member states are encouraged to strengthen their health systems and improve the monitoring of animal populations to detect potential disease outbreaks as early as possible. Global supply chains are to be adapted so that all countries have reliable access to protective equipment, medicines, and vaccines in times of crisis. In any future pandemic, healthcare workers should be given priority access to these essential supplies.

This is neither wild nor new. Stolpe says: "To build regional vaccine production capacities based on promising mRNA technology, the World Health Organization and the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) launched a program in 2021 that is still ongoing.

Groundhog Day: Donald Trump

However, established global supply chains in the research-based pharmaceutical industry are under acute threat from the US government's customs policy. Under the pretext of an alleged threat to US national security, Donald Trump wants to introduce special tariffs on pharmaceutical imports with the aim of significantly increasing his country's share of production.

Currently, about half of all patent-protected pharmaceuticals are produced in the US, with 35% originating in the European Union. “Since the US is not participating in the global pandemic agreement, there is reason to fear that it could introduce strict export controls on critical pharmaceuticals in the event of a new pandemic,” says Michael Stolpe. This concern highlights a broader gap in the agreement negotiations: complex financing issues have largely been left unresolved. Stolpe adds: “There are no concrete plans for major financial support — such as preventive measures in countries of the Global South — nor has it been clarified how the agreement’s implementation can be coordinated and monitored.”

There is still much work to be done.

The pandemic treaty is not the end of the story, but rather a starting point for building a more resilient global health system.

Dr. Michael Stolpe…

...is co-spokesperson for the Leibniz Lab Pandemic Preparedness and a member of the lab's steering committee. He is jointly responsible for the focus on pandemic management, which centers on the resilience of our healthcare system.

He also heads the Global Health Economics project area at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). His work focuses primarily on health inequality, health investments across the life cycle, methods of economic evaluation, and innovations in medical technology. Michael Stolpe has additional research experience in the areas of financial markets, international economic relations, and growth economics.

In the area of pandemic management, Stolpe's main focus is on work package 10: “Identification of elements of pandemic preparedness that should be regulated in a global pandemic treaty and development of a discourse-ethics-based strategy for agreeing on an enforceable treaty.”

Development of a discourse-ethics-based strategy for agreeing on an enforceable treaty.” Here, the IfW is leading the project together with the PRIF, the Leibniz Institute for Peace and Conflict Research.